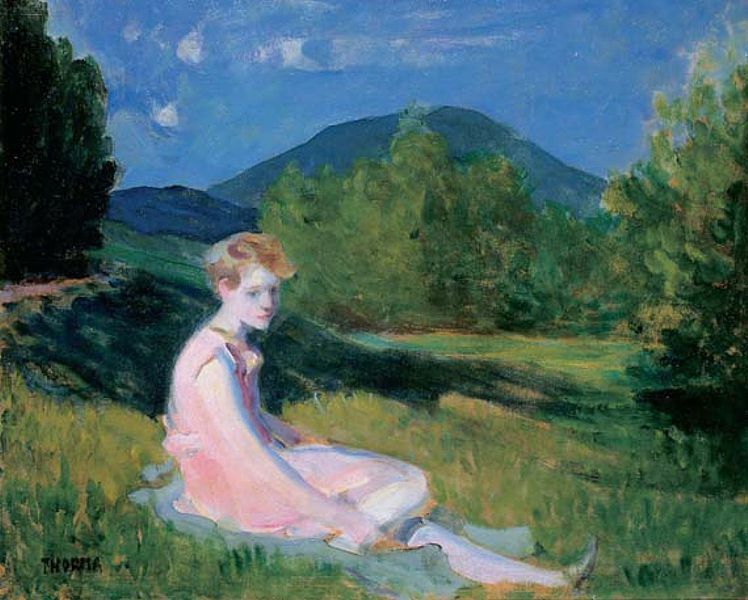

'The muse'

by William Henry Davies (1871 - 1940)

I have no ale,

No wine I want;

No ornaments,

My meat is scant.

No maid is near,

I have no wife;

But here's my pipe

And, on my life:

With it to smoke,

And woo the Muse,

To be a king

I would not choose.

But I crave all,

When she does fail --

Wife, ornaments.

Meat, wine and ale.

'A young woman mourning a dead dove, a partridge, and a kingfisher is a painting', 1620, Jacob de Gheyn II

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, (1770 - 1831). 'Philosophy of Nature'. 'Organics'.

A history of the Earth.

If you want to get into it you have to get out of it.

Hawkwind - 'Utopia':

++++

Nature in Hegel' embodies the necessary structures described in the 'Science of Logic' while extended out into space that is the realm of externality in contrast to human culture that develops by a complex process of internalizing its history through time, albeit regarding the dichotomy between matter and spirit in such a manner is much too much concealing its complexity given that nature incorporates its own modes of internalization and its own sort of external repetitive processes. Hegel was aware that the face of the earth had been formed by long-term geological processes that can be read in the current formations, and if rocks and hills have a temporal dimension then what is to be said regarding current natural kinds and the fossils discovered in those rocks?

Hegel rejected the theories of evolution current in his day yet was willing to accommodate the historical unfolding of the Idea of Nature... the philosopher of Spirit, the Absolute Idealist, whose concerns stretched from logic to society, and also paid a great deal of attention to nature and natural history. Why so? We ask having been told that nature is without a history. Hegel's lectures discuss at length history, religion, spirit, and logic while nature is treated more briefly in the second part of the 'Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences' with additional notes drawn from student records of these lectures but they are not so well connected with one another and those who prepared Hegel's lectures for publication after his death seemingly did not consider the lectures on nature to be in need of being assembled together whereas they assembled with varying degrees of success many years’ lectures upon history, art, and religion.

But Hegelian natural history is significant since with it an original way is presented on how to think about nature. And he was aligned with Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, (1775 – 1854), and other figures of German Romanticism who had creative theories of nature albeit he came to reject their overall views but his encounter with them left its impression upon him. And further, Hegel took an interest in the science of his day and was well informed concerning its developments and areas of dispute and perhaps he did not always align himself with what proved in the end to be the winning side but his observations upon them are still of interest and certainly penetrating. But as a philosophy of spirit, self-consciousness and culture there is not so much a romantic elation and jubilation of nature in itself nor does he follow Schelling in his endeavour to employ categories derived from nature to understand spirit and history. Hegel takes the dependence to proceed in the other direction whereby nature reveals to us structures and processes that reflect in primitive form the more developed processes disclosed through culture and history.

The Hegelian approach to studying Nature, his conceptual analysis of the natural world, is presented in his Encyclopedia and his 'Science of Logic', whereas to discover what it means to live in nature and to be confronted by its vigour and multifariousness one must delve into his texts on art and religion. The manner by which nature enters our lives is not to be expressed so as to sound like a romantic exaltation of nature nor are we to believe in an unreflective life in unity with nature the objective is rather not an connection that is immediate immediate but rather one that is a result:

'This unity of intelligence and intuition, of the being-in-self of spirit and its relation to externality, must however be the goal not the beginning; it must be a unity which is brought forth, not one which is immediate. The natural unity of thought and intuition found in a child or an animal is no more than feeling, it is not spirituality. Man must have eaten of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, he must have gone through the labour and activity of thought in order to be what he is, i.e. the subjugator of the separation of what is his, from nature. That immediate unity is therefore merely abstract, it is the being-in-self of truth, not the actuality of it; not only the content, but also the form must be true. The healing of the schism must have the shape of the form of the knowing Idea, and the moments of the healing must be sought in consciousness itself. It is not a matter of resorting to abstraction and vacuity and deserting knowledge; consciousness must preserve itself, so that ordinary consciousness may itself overcome the assumptions out of which the contradiction arose'.

- 'Philosophy of Nature'

We need to distance ourselves from any immediate feeling of unity and mythological identification with nature and then reintegrate ourselves with nature by studying it and finding there the lineaments of spirit hence we will be conducting a double study for the relation of the logical categories to nature have hitherto been incorrectly interpreted as the operation of a separate level of causality when instead their potency lies in defining the dispositions and potentialities of things. To begin with we derive through self-investigation of pure thought the logical categories necessary for thinking about any being on any level these being valid in both nature and culture and providing a metaphysical framework given that metaphysics is naught besides the entire range of the universal determinations a diamond net into which everything is brought and thereby first made intelligible:

'The philosophy of nature distinguishes itself from physics on account of the metaphysical procedure it employs, for metaphysics is nothing but the range of universal thought-determinations, and is as it were the diamond-net into which we bring everything in order to make it intelligible. Every cultured consciousness has its metaphysics, its instinctive way of thinking. This is the absolute power within us, and we shall only master it if we make it the object of our knowledge. Philosophy in general, as philosophy, has different categories from those of ordinary consciousness. All cultural change reduces itself to a difference of categories. All revolutions, whether in the sciences or world history, occur merely because spirit has changed its categories in order to understand and examine what belongs to it, in order to possess and grasp itself in a truer, deeper, more intimate and unified manner. The inadequacy of the thought determinations used in physics may be traced to two very closely connected points. (a) The universal of physics is abstract or simply formal; its determination is not immanent within it, and does not pass over into particularity. (b) This is precisely the reason why its determinate content is external to the universal, and is therefore split up, dismembered, particularized, separated and lacking in any necessary connection within itself; why it is in fact merely finite. Take a flower for example. The understanding can note its particular qualities, and chemistry can break it down and analyse it. Its colour, the shape of its leaves, citric acid, volatile oil, carbon, hydrogen etc., can be distinguished; and we then say that the flower is made up of all these parts'.

- 'Philosophy of Nature'

Every educated consciousness has its metaphysics an instinctive way of thinking the absolute power within us of which we become master only when we make it in turn the object of our knowledge and philosophy in general has as philosophy other categories than those of the ordinary consciousness, all education (Bildung) reduces to the distinction of categories and all revolutions in the sciences no less than in world history originate solely from the fact that spirit in order to understand and comprehend itself with a view to possessing itself has changed its categories comprehending itself more truly, more deeply, more intimately, and more in unity with itself and the result of the logical investigation is the absolute Idea which is the involuted final category that includes all the others as its moments and aspects of its self-referential unity. The content of the absolute Idea is its own self-development and the final section of the Logic reflects back upon the earlier sections and discerns the dialectical motions of its subsidiary concepts in particular the move from concepts describing simple immediate presence to kinds of mediated unities to self-differentiating unities that hold together unity and manifold variety.

Woman with a dead hare, 1675, Jacob Toorenvliet

'Eternity is not before or after time, it is not prior to the creation of the world, nor is it the sequel to its disappearance; it is absolute present, the now, and has no before or after. The world is created, is now being created, and always has been created; this becomes apparent in the conservation of the world. The activity of the absolute Idea is created; like the Idea as such, the Idea of nature is eternal. (b) If one asks whether the world, nature, in its finitude, has a beginning in time or not, one has the world or nature in general before one's mind, i.e. the universal; and it has already been shown that the true universal is the Idea, which is eternal. That which is finite is temporal however, and has a before and after; and if one has the finite as one's object, one is within time. That which is fmite has a beginning, but not an absolute beginning; its time begins with it, and there is no time without finitude. Philosophy is the timeless comprehension of everything in general according to its eternal determination, and including time'.

- 'Philosophy of Nature'

The key to understanding nature is a prior understanding of the internal distinctions and divisions within this complex conceptual unity, this is das Begriff, etymologically what grasps together, the standard German word for concept. The Concept or Notion as it is sometimes translated is not a single concept such as rabbit or cause but more like a whole set of categories with their complex internal connections mutually constituting one another and describing their own logical connections and transformations. And having derived categories that describe the way differing sorts of being and unity come together nature can then be studied as revealed by contemporary science for how it embodies the various moments of this complex movement. It begins with Logic, the basic categories are not derived from the always incomplete empirical sciences, one must begin from the Concept and even if perhaps the Concept is unable as yet to provide an adequate account of the abundant variety of Nature so-called one must nonetheless place one's faith in the Concept albeit many details are as yet to be explained. What does it mean to explain everything anyway? Failure to do so is no reflection upon the Concept whereas in the case of the theories of the empirical physicists the position is the reverse given that they must explain everything for their validity rests only on particular cases but the Concept is valid in its own right; the particulars then will soon find their explanation.

'In living existence, the higher natures are those in which the abstract moments of sensibility and irritability have a distinct existence; lower living existence is no more than reproduction, but in its higher natures it contains profounder differences and preserves itself in this more cutting diremption. Thus there are animals which are nothing but reproduction; they are an amorphous jelly, an active and intro-reflected slime, and in them there is as yet no distinction between sensibility and irritability. These are the general moments of animal being, but they are not to be regarded as properties, each of which acts in a particular way, as colour has a particular effect upon sight, and taste upon the tongue etc. It is true that nature also deploys the moments separately and in a state of reciprocal indifference, but it does this quite exclusively in the shape, i.e. in the dead being of the organism. Nothing in nature is as distinct in itself as is the animal, but as its nature is the speculative Notion, nothing is so difficult to grasp. Despite the animal's having the nature of a sensuous existence, it still has to be grasped in the Notion. In sensation, living existence exhibits supreme simplicity, for everything else is a mutual externality of qualities. Yet at the same time, living existence is fully concrete, for it allows the moments of the Notion, which have reality in a single subject, to assume a determinate being. Lifeless existence is abstract however. In the solar system, the Sun corresponds to sensibility, comet and Moon constitute the moments of difference, and the planet is reproduction. In the system each body is an independent member however, while in the case of the animal, the members are contained in a single subject. This idealism, which recognizes the Idea throughout the whole of nature, is at the same time realism, for the Notion of living existence is the Idea as reality, even though in other respects the individuals only correspond to one moment of the Notion. In real, sensuous being, philosophy recognizes the Notion in general. One must start from the Notion, and even if it should as yet be unable to exhaust what is called the 'abundant variety' of nature, and there is still a great deal of particularity to be explained, it must be trusted nevertheless. The demand that there should be an explanation for this particularity is generally vague, and it is no reflection on the Notion that it is not fulfilled. With the theories of the empirical physicists the position is quite the reverse however, for as their validity depends solely upon singular instances, they are obliged to explain everything. The Notion holds good of its own accord however, and singularity will therefore yield itself in due course'.

- 'Philosophy of Nature'

It is possible to trace how nature approaches more closely to spirit's unity-in-difference as we study more and more complex natural systems and organisms and we can works with a priori definitions of what it means to be a mechanism, a chemical unity, an organism while leaving it to empirical contingencies precisely what develops to fulfill these definitions. General categorial structure is to be distinguished from the contingent detail of nature and the Logic shows the general types that must be thought but no natural being appears as only a general type and what philosophy delivers is the general scheme so that we know for instance that an animal organism must have subsystems for mobility, perception, for gathering energy from its environment yet whether it has two legs or eight, one eye or a hundred, and what precise species of bird it is, these are contingent details.

And furthermore, how the organism came to have its particular features is an empirical question that is not of philosophical interest rather the investigation is somewhat akin to devising a periodic table of the elements than an evolutionary tree and in declaring that nature has no history what is meant is not that individual species were eternal but rather that the logical categories for nature’s general types were derived and valid in pure thought without reference to empirical history. Spirit aims at becoming fully self-present to and in its own complex unity and development and that development requires that each of the basic moments and aspects studied by the logic be explicitly brought forward to be posited more or less independently on its own and then be brought back into a bigger overarching unity. Spirit develops by having all its logically necessary moments and movements posited outside and then brought inside its self-awareness and in this development everything is interdependent despite initial appearances of separation and nothing stands purely on its own and everything is mediated through relations and processes with other aspects, moments, and things that in their turn are mediated.

Their interrelation may be simplified and mechanical yet there is forever interrelation and there are no simple units that can be fully just what they are without any connection to anything else and there is no level of fundamental totally independent atomic entities in nature nor in psychology, thought, or society. In every area theories that postulate a basic layer of isolated independent entities (material atoms, isolated sense data, pre-social rational individuals, self-contained concepts) with no necessary connections to one another and to larger unities are to be opposed. What is fundamental is the logical structure of the processes of mediation and interaction which led Hegel to deny the atomic theory of chemistry as it was proposed in his day and he was mistaken about that but correct in his emphasis for even then the atomic theory was no longer a theory of fundamentally self-sufficient independent entities. Newton's theory of gravity compromised the strict independence of the atoms new observations of chemical and electric forces were undermining strict atomism and today atoms are even less independent and self-sufficient given that their particles are also waves and transform themselves into one another while quantum non-local effects and decoherence indicate further entanglements yet to be fully understood.

Nature's levels of increasingly complex empirical interrelations can be viewed as developing over time though that is not of principle philosophical interest but what is is that Nature's fertility operates both in the past and the corn is not so much to tracing the details of what developed from what but to demonstrate how the different logical moments of spirit's processes were embodied externally in nature's immense variety. Hegel understood the bountiful variety of nature and followed Aristotle in distinguishing the three broad categories of mineral, vegetable, and animal but he was also cognisant of the fact that the world revealed through the microscope showed vast new ranges of living things, among which of particular interest to him was was plankton and other tiny creatures that show the ocean to be a natural womb from which life constantly emerges, the fecundity of the Earth causes life to break forth everywhere and in every way.

'The immediacy of the Idea of life consists of the Notion as such failing to exist in life, submitting itself therefore to the manifold conditions and circumstances of external nature, and being able to appear in the most stunted of forms; the fruitfulness of the earth allows life to break forth everywhere, and in all kinds of ways. The animal world is perhaps even less able than the other spheres of nature to present an immanently independent and rational system of organization, to keep to the forms which would be determined by the Notion, and to proof them in the face of the imperfection and mixing of conditions, against mingling, stuntedness and intermediaries. The feebleness of the Notion in nature in general,! not only subjects the formation of individuals to external accidents, which in the developed animal, and particularly in man, give rise to monstrosities, but also makes the genera themselves completely subservient to the changes of the external universal life of nature. The life of the animal shares in the vicissitudes of this universal life (cf. Remark § 392), and consequently, it merely alternates between health and disease. The milieu of external contingency contains very little that is not alien, and as it is continually subjecting animal sensibility to violence and the threat of dangers, the animal cannot escape a feeling of insecurity J anxiety and misery'.

- 'Philosophy of Nature'

Hegel also read reports regarding types of animals that differed from those alive today and he interpreted the fossil record as showing extinct species and experimental forms intermediate between the usual types and he claimed that these along with present-day intermediate forms such as the platypus disclose both nature's fertility and its inability to embody precise categorical distinctions. Less almost than even than the other spheres of nature can the animal world exhibit within itself an independent rational system of organization or hold fast to the forms prescribed by the Concept, preserving them in face of the imperfection and medley of conditions from confusion, degeneration, and transitional forms.

'Consequently, the infinity of forms exhibited by animal being is not to be pedantically regarded as conforming absolutely to the necessary principle of orders. The general determinations must be made to rule therefore, and the natural forms compared with them. If the natural forms do not tally with this rule, but exhibit certain correspondences, agreeing with it in one respect but not in another, then it is not the rule, the determinateness of the genus or class etc. which has to be altered. The rule does not have to conform to these existences, they ought to conform to the determinateness, and this actuality exhibits deficiency in so far as it fails to conform. Some Amphibia are viviparous for example, and like Mammals and Birds, breathe by means of lungs; in that they have no breasts, and their heart has a single ventricle, they resemble Fish however. If one is prepared to admit that the works of man are sometimes defective, it must follow that those of nature are more frequently so, for nature is the Idea in the mode of externality. In man, the basis of these defects lies in his whims, his caprice and his negligence, e.g. when he introduces painting into music, paints with stones in mosaics, or introduces the epic genre into drama. In nature, it is the external conditions which stunt the forms of living being; however, these conditions produce these effects because life is indeterminate, and also because it is from these externalities that it derives its particular determinations. The forms of nature cannot be brought into an absolute system therefore, and it is because of this that the animal species are exposed to contingency'.

- 'Philosophy of Nature'

The variety of nature surpasses the set of categories that Hegel contended are the a priori structure of nature but rather than this undermining the categories it demonstrates that in its externality nature is not able to embody the full complexities of the logical concept.

'Woman Scraping Carrots', Gerrit Dou (1613–1675)

Outsides. Nature is the primal and ultimate outside whereby the different levels and types within nature exist spread out in space externally connected to one another and individual natural things in their turn display sets of properties that may have no necessary connections and the contradiction of the Idea arising from the fact that as nature it is external to itself is more exactly this, that on the one hand there is the necessity of its forms which is generated by the Concept and their rational determination in the organic totality while on the other hand there is their indifferent contingency and indeterminable irregularity. In the realm of nature contingency and determination from without has its right and this contingency is at its greatest in the realm of concrete individual forms that nonetheless as products of nature are concrete only in an immediate manner, and the immediately concrete thing is a group of properties external to one another and more or less indifferently related to each other and for that reason the simple subjectivity that exists for itself is also indifferent and abandons them to contingent and external determination, and this is the impotence of nature, that it preserves the determinations of the Concept only abstractly and leaves their detailed specification to external determination.

'In so far as the contradiction of the Idea is external to itself as nature, one side of it is formed by the Notionally generated necessity of its formations and their rational determination within the organic totality, and the other by their indifferent contingency and indeterminable irregularity. In the sphere of nature, contingency and determinability from without come into their own. This contingency is particularly prevalent in the realm of concrete individual formations, which are at the same time only immediately concrete as things of nature. That which is immediately concrete is in fact an ensemble of juxtaposed properties, external and more or less indifferent to one another, to which simple subjective being-for-self is therefore equally indifferent, and which it consequently abandons to external contingent determination. The impotence of nature is to be attributed to its only being able to maintain the determinations of the Notion in an abstract manner, and to its exposing the foundation of the particular to determination from without'.

- 'Philosophy of Nature'

Nonetheless this externality is not the complete picture rather the Hegelian picture of nature is a complex balance between individuals that display the different aspects of spirit and interactions that connect them into natural wholes and nature's variety is not just a heap of completely separate items. Gravity unites separated bodies into physical systems, chemistry and electricity demonstrate how apparent independent beings intimately influence one another, different organisms form complex networks as they share space, rely upon and prey upon one another, yet these sorts of dependencies remain external and do not form a tight unity such as is found inside a single organism or in the history of self-aware individuals and cultures. Hegel desists from aligning himself with the Stoics for whom nature as a whole is a single living organism in which each thing keeps to its appointed role. Nature's externality means that there will be many different unities and kinds of unity all expressing the Concept but unable to come together into a whole in the way spirit can unify and totalize itself in politics and community and more completely in art religion, and philosophy.

The entire Concept is there at every level of nature present but not in its fully explicit and mediated unity, for example in the abstract consideration of matter we observe both the self-division of the Concept in the separate points of space and its unity in the gravity that holds space and its contents together, and to demonstrate the different levels of unity in nature Hegel on several occasions compares the solar system with an animal organism whereby in the solar system different aspects of the Concept are embodied in the different motions of the planets, moons, and comets that exist as independent bodies externally related to one another and the unity of the system is expressed abstractly as the gravitational force that holds them together and concretely in the existence of the sun as the center of the system. The Sun, comets, moons, and planets appear on the one hand as heavenly bodies independent and different from one another yet on the other hand they are what they are only because of the determined place they occupy in the total system of bodies.

Their specific kind of movement as well as their physical properties can be derived only from their situation in the system and such interconnection constitutes them in the unity that relates their particular existence to one another and holds them together and yet the Concept cannot halt at this purely implicit unity of the independently existing particular bodies for it has to make real not only its distinctions but also its self-relating unity. And this unity now distinguishes itself from the mutual externality of the objective particular bodies and acquires for itself at this stage in contrast to this mutual externality, a real bodily independent existence. For instance in the solar system the sun exists as this unity of the system over against the real differences within it yet the existence of the ideal unity in this way is itself still of a defective kind for on the one hand it becomes real only as the relation together of the particular independent bodies and their bearing on one another and on the other hand as one body in the system.

'In the world of nature we must at once make a distinction in respect of the manner in which the Concept, in order to be as Idea, wins existence in its realization. ... higher natural objects set free the distinctions of the Concept, so that now each one of them outside the others is there for itself independently. Here alone appears the true nature of objectivity. For objectivity is precisely this independent dispersal of the Concept's distinctions. Now at this stage the Concept asserts itself in this way: since it is the totality of its determinacies which makes itself real, the particular bodies, though each possesses an independent existence of its own, close together into one and the same system. One example of this kind of thing is the solar system. The sun, comets, moons, and planets appear, on the one hand, as heavenly bodies independent and different from one another; but, on the other hand, they are what they are only because of the determinate place they occupy in a total system of bodies. Their specific kind of movement, as well as their physical properties, can be derived only from their situation in this system. This interconnection constitutes their inner unity which relates the particular existents to one another and holds them together'.

- 'Aesthetics'

'Yet at this purely implicit unity of the independently existing particular bodies the Concept cannot stop. For it has to make real not only its distinctions but also its self-relating unity. This unity now distinguishes itself from the mutual externality of the objective particular bodies and acquires for itself at this stage, in contrast to this mutual externality, a real, bodily, independent existence. For example, in the solar system the sun exists as this unity of the system, over against the real differences within it. But the existence of the ideal unity in this way is itself still of a defective kind, for, on the one hand, it becomes real only as the relation together of the particular independent bodies and their bearing on one another, and, on the other hand, as one body in the system, a body which represents the unity as such, it stands over against the real differences. If we wish to consider the sun as the soul of the entire system, it has itself still an independent persistence outside the members of the system which are the unfolding of this soul. The sun itself is only one moment of the Concept, the moment of unity in distinction from the Concept's real particularization, and consequently a unity which remains purely implicit and therefore abstract. For the sun, in virtue of its physical quality, is the purely identical, the giver of light, the Iight-body as such, but it is also only this abstract identity. For light is simple undifferentiated shining in itself.-So in the solar system we do find the Concept itself become real, with the totality of its distinctions made explicit, since each body makes one particular factor appear, but even here the Concept still remains sunk in its real existence; it does not come forth as the ideality and the inner independence thereof. The decisive form of its existence remains the independent mutual externality of its different factors'.

- 'Aesthetics'

'The infinite divisibility of matter simply means that it is external to itself. It is precisely this externality which we first wonder at in the immeasurability of nature. Thoughts are not co-ordinated in nature, for Notionlessness holds sway here, and each material point appears to be entirely independent of all the others. The sun, planets, comets, elements, plants, animals, all exist as self-contained particulars. The sun is not one and the same individual as the earth, and is only bound to the planets by gravity. Subjectivity is first encountered in life, which is the opposite of extrinsicality. The heart, liver, eye are not independent individualities on their own account; the hand, severed from the body, decays. The organic body is still a whole composed of a multiplicity of mutually external members, but each individual organ subsists only in the subject, and the Notion exists as the power which unites them. In this way the Notion, which is something merely inward in Notionlessness, first comes into existence in life, as soul. The spatiality of the organism is completely devoid of truth for the soul; if this were not so, we should have as many souls as points, for the soul feels at every point. One should not allow oneself to be deceived by the appearance of extrinsicality; one should remember that the mutual externality constitutes only a single unity. Although they appear to be independent, the celestial bodies have to patrol a single field. Since unity in nature is a relation between apparently self-subsistent entities however, nature is not free, but merely necessary and contingent. Necessity is the inseparability of terms which are different, and yet appear to be indifferent. The abstraction of self-externality also receives its due there however, hence the contingency or external necessity, contrasting with the inner necessity of the Notion. In physics a lot has been said about polarity, and ills concept has marked a great advance in the metaphysics of physics, for as a concept it is nothing more nor less than the determination of the necessary relationship between two different terms, which, in so far as the positing of one is also the positing of the other, constitute a unity. Polarity of this kind limits itself only to the opposition; it is by means of the opposition however that there is also a positing of the return out of the opposition into unity, and it is this third term which constitutes the necessity of the Notion, a necessity which is not found in polarity. In nature taken as otherness, the square or tetrad also belongs to the whole form of necessity, as in the four elements, the four colours etc.; the pentad may also be found, in the five fingers and the five senses for example; but in spirit the fundamental form of necessity is the triad. The totality of the disjunction of the Notion exists in nature as a tetrad, the first of which is universality as such. The second term is difference, and appears in nature as a duality, for in nature the other must exist for itself as an otherness. Consequently, the subjective unity of universality and particularity is the fourth term, which has a further existence as against the other three. In themselves the monad and the dyad constitute the entire particularity, and the totality of the Notion itself can therefore proceed to the pentad'.

- 'Philosophy of Nature'

To be continued ...