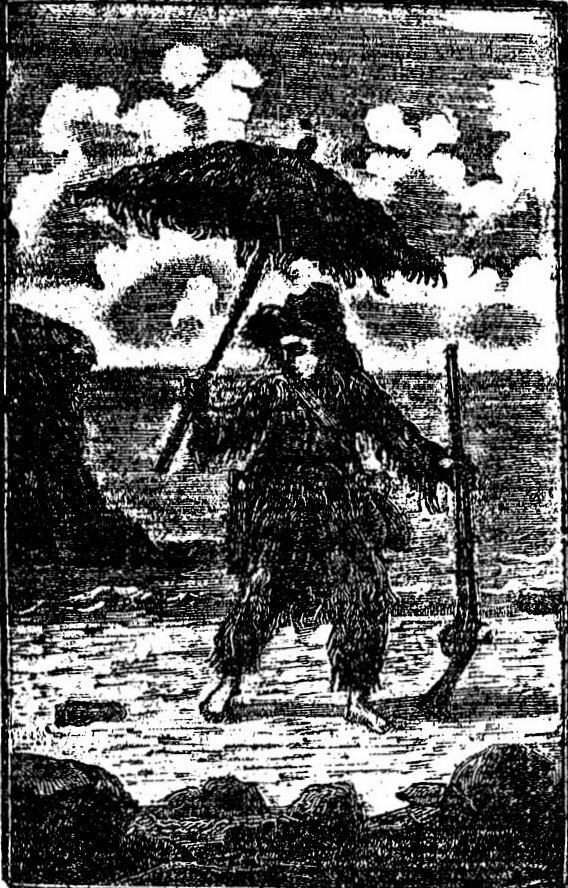

Robinson Crusoe struck with confusion and horror, at seeing the print of a man's foot upon the sand.

Robinson Crusoe struck with confusion and horror, at seeing the print of a man's foot upon the sand.

In this project I likewise found additional blessings; for I not only had plenty of goat's flesh, but milk too, which in my beginning I did not so much as think of. And, indeed, though I had never milked a cow, much less a goat, or seen butter or cheese made, yet, after some essays and miscarriages, I made the both, and never afterwards wanted.

How mercifully can the omnipotent Power comfort his creatures, even in the midst of their greatest calamities? How can be sweeten the bitterest providences, and give us reason to magnify him in dungeons and prisons? what a bounteous table was here spread in a wilderness for me, where I expected nothing thing at first but to perish for hunger.

Certainly a Stoic would have smiled to see me at dinner. There sat my royal majesty, and absolute prince and ruler of my kingdom, attended by my dutiful subjects, whom, if I pleased, I could either hang, draw, quarter, give them liberty, or take it away. When I dined, I seemed a king eating alone, none daring to presume to do so till I had done. Poll, as if he had been my principal court favorite, was the only person, permitted to talk with me. My old but faithful dog, now grown exceedingly crazy, and who had no species to multiply his kind upon, continually sat on my right hand; while my two cats sat on each side of the table, expecting a bit from my hand, as a principal mark of my royal favour. These were not the cats I had brought from the ship; they had been dead long before, and interred near my habitation by mine own hand. But one of them, as I suppose, generating with a wild cat, a couple of their young I had made tame; the rest ran wild into the woods, and in time grew so impudent as to return and plunder me of my stores, till such time as I shot a great many, and the rest left me without troubling me any more. In this plentiful manner did I live, wanting for nothing but conversation. One thing indeed concerned me, the want of my boat; I knew not which way to get her round the island. One time I resolved to go along the shore by land to her; but had any one in England met such a figure, it would either have affrighted them, or made them burst into laughter; nay, I could not but smile myself at my habit, which I think in this place will be very proper to describe.

The cap I wore on my head, was great, high, and shapeless, made of a goat's skin, with a flap of pent-house hanging down behind, not only to keep the sun from me, but to shoot the rain off from running into my neck, nothing being more pernicious than the rain falling upon the flesh in these climates. I had a short jacket of goat's skin, whose hair hung down such a length on each side, that it reached down to the calves of my legs. As for shoes and stockings, I had none, but made a semblance of something, I know not what to call them; they were made like buskins, and laced on the sides like spatterdashes, Barbarously shaped like the rest of my habit. I had a broad belt of goat's skin dried, girt round me with a couple of thongs, instead of buckles; on each of which, to supply the deficiency of sword and dagger, hung my hatchet and saw. I had another belt, not so broad, yet fastened in the same manner, which hung over my shoulder, and at the end of it, under my left arm, hung two pouches, made of goat's skin, to hold my powder and shot. My basket I carried on my back, and my gun on my shoulder; and over my head a great clumsy ugly goat's skin umbrella; which, however, next to my gun, was the most necessary thing about me. As for my face, the colour was not so swarthy as the Mulattoes, or might have been expected from one who took to little care of it, in a climate within nine or ten degrees of the equinox. At one time my beard grew so long that it hung down about a quarter of a yard; but as I had both razors scissors in store, I cut it all off, and suffered none to grow, except a large pair of Mahometan whiskers, the like of which I had seen wore by some Turks at Sallee, not long enough indeed to hang a hat upon, but of such a monstrous size, as would have amazed any in England to have seen.

But all this was of no consequence here, there being none to observe my behavior or habit. And so, without fear and without controul, I proceeded on my journey, the prosecution of which took me up five or six days. I first travelled along the sea shore, directly to the place where I first brought my boat to an anchor, to get upon the rocks; but now having no boat to take care of, I went overland a nearer way to the same height that I was before upon; when looking forward to the point of the rock, which lay out, and which I was forced to double with my boat, I was amazed to see the sea so smooth and quiet, there being no ripling motion, nor current, any more than in other places. This made me ponder some time to guess the reason of it, when at last I was convinced that the ebb setting from the west, and joining with the current of water from some great river on shore, must be the occasion of these rapid streams; & that, consequently, as the winds blew more westwardly, or more southwardly, so the current came he nearer, or went the farther from the shore. To satisfy my curiosity, I waited there till evening, when the time of ebb being made, I plainly perceived from the rock the current again as before, with the difference that it ran farther off, near half a league from the shore, whereas in my expedition, it set close upon it, furiously hurrying me and my canoe along with it, which at another time would not have done. And now I was convinced, that, by observing the ebbing and flowing of the tide I might easily bring my boat round the island again. But when I began to think of putting it in practice, the remembrance of the late danger, struck me with such horror, that I changed my resolution, and formed another, which was more safe, though more laborious; and this was to make another canoe, and to have one for one side of the island, and one for the other.

I had now two plantations in the island; the first my little fortification, fort, or castle, with many large and spacious improvements; for by this time I had enlarged the cave behind me with several little caves, one with another, to hold my baskets, corn, and straw. The piles with which I made my wall were grown so lofty and great as obscured my habitation. And near this commodious and pleasant settlement, lay my well cultivated and improved corn-fields, which kindly yielded me their fruit in the proper season. My second plantation was that near my country seat, or little bower, where my grapes flourished, and where, having planted many stakes, I made inclosures for my goats, so strongly fortified by labour and time, that it was much stronger than a wall, and consequently impossible for them to break through. As for my bower itself, I kept it constantly in repair, and cut the trees in such a manner, as made them grow thick and wild, and form a most delightful shade. In the centre of this stood my tent, thus erected. I had driven four piles in the ground, spreading over it a piece of the ship's sail; beneath which I made a sort of couch with the skins of the creatures I had slain, and other things; and having laid thereon one of the sailor's blankets, which I had saved from the wreck of the ship, and covering myself with a great watch-coat, I took up this place for my country retreat.

Very frequently from this settlement did I use to visit my boat, and keep her in very good order. And sometimes I would venture in her a cast or two from shore, but no further, lest either a strong current, a sudden stormy wind, or some unlucky accident should hurry me from the island as before. But now I entreat your attention, whilst I proceed to inform you of a new, but most surprising scent of life which there befel me.

You may easily suppose, that, after having been here so long, nothing could be more amazing than to see a human creature. One day it happened, that going to my boat I saw the print of a man's naked foot on the shore, very evident on the sand, as the toes, heel, and every part of it. Had I seen an apparition in the most frightful shape, I could not have been more confounded. My willing ears gave the strictest attention. I cast my eyes around, but could satisfy neither the one nor the other, I proceeded alternately in every part of the shore, but with equal effect; neither could I see any other mark, though the sand about it was as susceptible to take impression, as that which was so plainly stamped. Thus struck with confusion and horror, I returned to my habitation, frightened at every bush and tree, taking every thing for men; and possessed with the wildest ideas. That night my eyes never closed. I formed nothing but the most dismal imaginations, concluding it must be the mark of the devil's foot which I had seen. For otherwise how could any mortal come to this island? where was the ship that transported them? & what signs of any other footsteps? Though these seemed very strong reasons for such a supposition, yet (thought I) why should the devil make the print of his foot to no purpose, as I can see, when he might have taken other ways to have terrified me? why should he leave his mark on the other side of the island, and that too on the sand, where the surging waves of the ocean might soon.

have erased the impression. Surely this action is not consistent with the subtility of Satan, said I to myself; but rather must be some dangerous creature, some wild savage of the main land over against me, that venturing too far in the ocean, has been driven here, either by the violent currents or contrary winds; and not caring to stay on this desolate island, has gone back to sea again.

Happy, indeed, said I to myself, that none of the savages had seen me in that place: yet I was not altogether without fear, lest, having found my boar, they should return in numbers and devour me; or at least carry away all my corn, and destroy my flock of tame goats. In a word, all my religious hopes vanished, as though I thought God would not now protect me by his power, who had so wonderfully preserved me so long.

What various chains of Providence are there in the life of man! How changeable are our affections, according to different circumstances! We love to-day, what we hate to-morrow; we shun one hour, what we seek the next. This was evident in me in the most conspicous manner: For I, who before had so much lamented my condition, in being banished from all human kind, was now even ready to expire, when I considered that a man had set his foot on this desolate island. But when I considered my station of life decreed by the infinitely wise and good providence of God, that I ought not to dispute my Creator's sovereignty, who has an unbounded right to govern and dispose of his creatures as he thinks convenient; and that his justice and mercy could either punish or deliver me: I say when I considered all this, I comfortably found it my duty to trust sincerely in him, pray ardently to him, and humbly resign myself to his divine will.

Daniel Defoe (1719)

Daniel Defoe (1719)

Thank you for your support of Through the Looking Glass and for being a patron of science and the arts.

Best wishes!

~ Pearl Andersen

“Only art and science make us suspect the existence of life to a higher level, and maybe also instill hope thereof.”

~ Ludwig van Beethoven